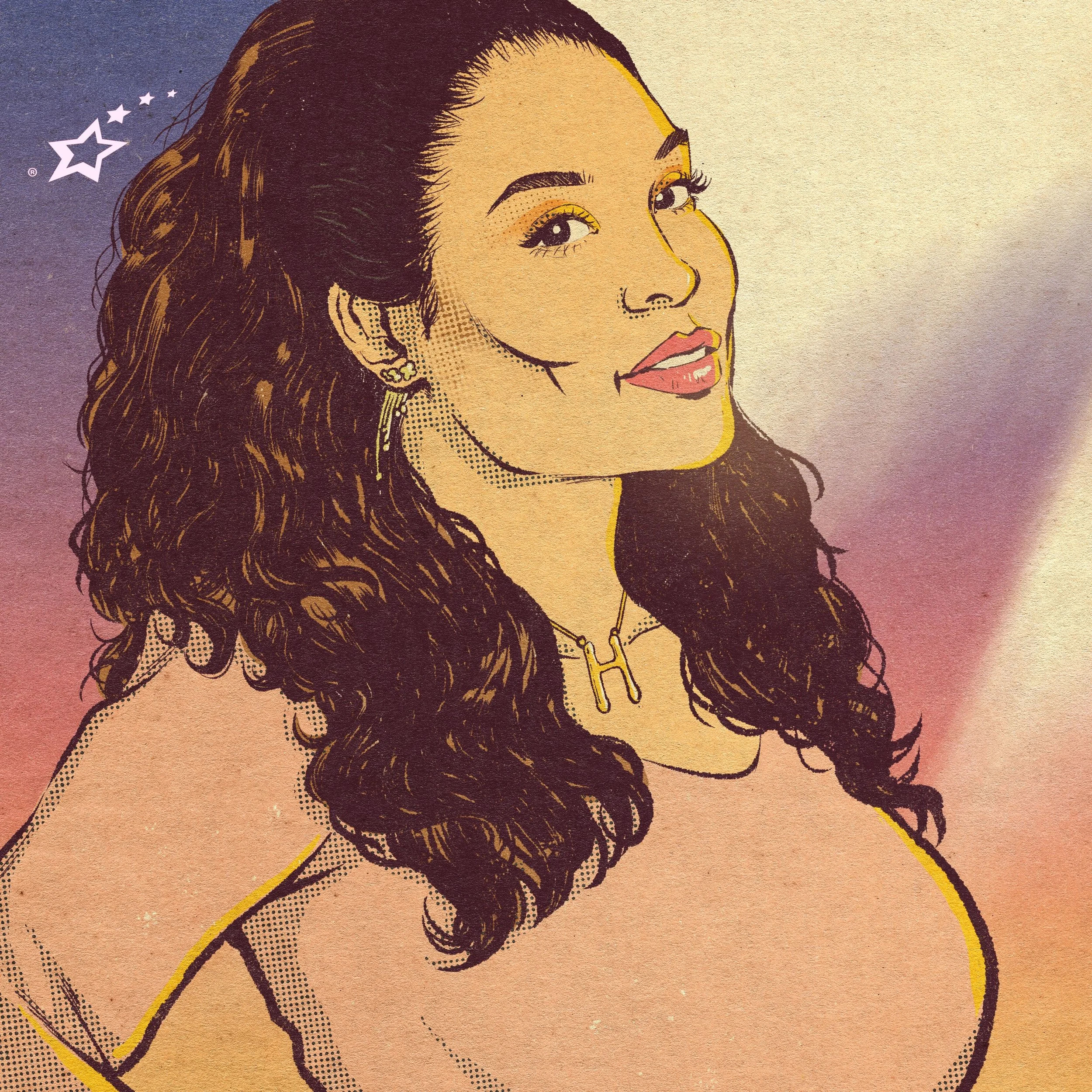

Her Melody

Honoré

Feature Interview

A note repeated, like a toast – a silver spoon tapping on crystal. Then the sweet, gorgeous sound of strings from an 18-piece orchestra plays a motif that descends with warmth, an arrangement that would have made the maestros of Philly-Soul proud. The groove locks in, held steady by the Detroit Lovers, a crew of first-call session players. Over the top, a voice glides, full of character and confidence – a vintage for connoisseurs, somewhere between Deniece Williams and Angela Bofill. “Innocent & Real” – an original composition by singer-songwriter Honoré – radiates opulence and spirit rare on today’s independent soul records.

“Oh my gosh, these chords are my happy place,” says Honoré – born Maureen Honoré in Detroit, now performing under her surname alone (pronounced “honour-ray”) – speaking from her apartment in Toronto. She explains what inspired her not just to pursue music, but to bring it with all the ethereal magic of the glory era of soul, Motown, ‘70s Stax & Philly.

“These challenging, delicious chords are my happy place. It was the vision I had – and it was a big fucking vision,” she says with a smile, dimples showing. On a bright, tranquil morning, she looks relaxed in a soft, blossom-pink blouse, her hair worn loose. “It was a soul vision to do it how they did when I was little, with that real love for the music.”

On the strength of “Innocent & Real” and the equally lush “It’s Over” – paired for an exclusive double A-side vinyl release on Soul Jones Records – listeners have compared her remarkable five-octave range to the sweet songbirds of the seventies, inspirations she readily acknowledges.

“Before this interview, did you read up on my affinity for Deniece Williams?” she asks. I hadn’t. “No? Holy shit! Well, you’re right. Deniece is one of the singers who told me my voice is acceptable. Her, Minnie Riperton, Smokey Robinson – they showed me I didn’t need to be afraid my voice wasn’t as thick and chocolatey as Chaka, Luther, Teddy or Phyllis. There was a place for me. People would like it, because I sure like listening to them.” She says it humbly, seemingly unaware that few singers possess the delicate timbre and range of Deniece, Minnie – or Honoré.

“I wanted to create this for me so that when I’m 75 and looking back, I can say, ‘Oh man, you were great then. Thanks, me!’”

At first, she didn’t feel ready to make a soul record. After falling for a Canadian – a “hot Torontonian,” she laughs, describing her now-husband, for whom “Innocent & Real” was written – she relocated north of the border. Wary of soul being seen as indulgent, she set her sights instead on a jazz EP, believing the genre would be more eagerly accepted in her new surroundings. (In Toronto’s St Clair district, where I was based for this assignment, a Canadian jazz radio station plays over tannoys lining the streets.) But a mislaid grant proposal nearly ended her solo career before it began.

“I was so upset, because the proposal was splendid, absolutely fucking splendid,” she says. “But months passed after my peers had heard back, and I hadn’t. I thought maybe I shouldn’t do music. But then I asked myself, why are you doing this really? It was a smokescreen to get the funds to do the soul record. And even though it felt like the only person who wanted to hear it was me, I thought, why not just do the thing you’re afraid of? The soul thing. I may be older, but there’s still sap in this tree, still electricity and excitement. I wanted to create this for me so that when I’m 75 and looking back, I can say, ‘Oh man, you were great then. Thanks, me!’”

To do it authentically – with full MFSB-style orchestration and Detroit players who know it’s what’s in the groove that counts – she funded the project herself, using savings and her nine-to-five income, painstakingly bringing to life a whole album due in early 2026, almost entirely self-written.

“I had to do the record in batches, because this was just me with my little day job. I don’t have much – but I’ve got champagne taste.”

A turning point came with the involvement of two producers: Maurice “Pirahnahead” Herd – whose credits include Victoria Monét, Sy Smith, De La Soul & Kem – and Thomas McKay (Nightcrawlers; Five Guys Named Moe), Juno nominated and known for work with Soulful Emma Louise, Charles Bradley, Dahlia Fernandez and Denielle Bassels.

Honoré first encountered Pirahnahead outside United Sound in Detroit – the studio where Aretha Franklin worked on Who’s Zoomin’ Who?, Marvin Gaye recorded much of What’s Going On, and the strings for Isaac Hayes’s Hot Buttered Soul were cut. He was perched on a concrete surround, swinging his legs and smoking, when she arrived to sing with the Sacred Heart choir. They looked at each other and said, simultaneously, “Don’t I know you?” Though they had never met – she from the west side, he from the east – they clicked instantly.

“I’ve got champagne taste.”

“It was one of those moments where it felt like meeting someone you’d known in a previous life.”

A protégé of Motown arranger Paul Riser and a friend of Benjamin Wright, Pirahnahead had absorbed lessons from the masters – carrying the torch held by Riser, Van McCoy, Gene Page, Bobby Martin and Thom Bell. (Check out Pirahnahead’s strings on Frankie Zulferino’s “Drippin’ in Love”, too. Pure Thom Bell-style brilliance. Masterful.)

“That was the first time I’d sat with a producer where I could sing little parts of what I envisioned – and they got it.”

When Honoré writes songs, she hears the full orchestration in her head. “Innocent & Real” was conceived sat in the front of the car, whilst chatting with Pirahnahead. “I started singing, doo-do-doo-do-doo-DID-DID!” she laughs, recalling how she sang the melody for the string intro. Pirahnahead understood what to do, writing the charts for his players – the Detroit Soulchestra – recording at his Rustbelt Studio in Michigan.

Detroit’s finest formed the session band Detroit Lovers, a Funk Brothers-style collective. On this record they included drummer Ron Otis – uncannily reminiscent of Earl Young – having learned his chops playing with Aretha Franklin, Nancy Wilson, SWV and Bob James. Bassist Takashi Iio, a nine-time Detroit studio musician of the year award winner who counts James Jamerson & Bernard Edwards as heroes. Wayne Gerard supplied the wah-wah flourish on “It’s Over”, having worked with Stevie Wonder, Grover Washington and Lenny White. Keyboardist Antony Gordon – whose credits include the Dramatics, Glenn Jones and Alexander O’Neal – lights up the instrumental break on “Innocent & Real”. “Man, I just see music in colours,” he says, explaining his approach.

Canadian producer and guitarist Thomas McKay, who recorded all Honoré’s vocals at Exeter Sound Studio in Toronto, was equally integral.

“That was the first time I’d sat with a producer where I could sing little parts – and they got it.”

“It was another thunderbolt – it’s only happened three times: Pirahna, my husband Kevin, and Thom. The first time I met Thom, at his studio, I pointed at him shouting, ‘I know you! I really know you!’ I was screaming like a fucking idiot, and honestly, he looked a little scared.” Honoré says and bursts into laughter.

On any given day you’ll find Thom dressed in black, shades on, ready to record. A proper Canadian, his “about” sounds like “a-boot” – though with a British interviewer he’ll often drop into what he thinks is fluent cockney, betraying his years in the UK with hit group the Nightcrawlers. A seasoned multi-instrumentalist, his studio houses a grand piano, a sitar, and a custom guitar forged in a secret Wiltshire location – “round the corner from Stone’enge!” as he puts it – all among the musical arsenal at his disposal. The stairway to the studio is lined with awards, tour posters and memorabilia – including a picture of Sly Stone and the sheet music for another forthcoming co-write with Honoré, “Ain’t No Substitute”.

“All the people attached to this thing – somehow, someway – the universe assembled and put me on this path.”

That pathway had been long and winding and like many soul stories, it started at home. Honoré was raised in Detroit by Creole parents who originally hailed from central Louisiana – Black, French and Native American (Avoyel tribe). She’s related to Jelly Roll Morton on her dad’s side and Little Walter on her mum’s.

She grew up in a house filled with sound – not just Motown and gospel but what she calls “beige soul”: Gino Vannelli, Bobby Caldwell, Hall & Oates. Honoré even auditioned for and attended a masterclass with Vannelli. “He was one of my heroes and one of the main people who put me on this path. He’s so elegant in everything. He told me” – Honoré clears her throat and effects a suave and sophisticated voice – “‘You know, this journey is worth taking – but if you tug on the tiger’s tail, it might just turn around!’”

“I literally died.”

Her earliest memory of performing for a crowd was in grade school. “Mrs McCall was at the piano, heard me amongst the other kids and said, ‘You… you sing this,’ and I remember she had me sing “Bring a Torch” for a Christmas concert.” In high school she took up clarinet – until a life-changing event.

“I literally died,” says Honoré, recalling how, at 14 years old, she closed a door to dance with abandon to Paula Abdul’s “Straight Up”, not realising a broken mirror was propped behind it. Sliding on the carpet in socks, she fell back and impaled her wrist, bleeding out until she lost consciousness. Her family saved her life. “It was a slow death – immense, cool, strangely awesome,” she says of her brush with the other side. “I’ve thought about it for decades, trying to make sense of it.”

Her left hand was left partly disabled. “Just like Django Reinhardt, these three fingers are unable to move independently,” she says, before joking, “I can’t hold money in that hand!” She continues: “It was a freak accident, but when I came back, I went all-in on singing because I couldn’t play clarinet anymore.”

She joined a small jazz group curated by music teacher, Mr. Miller – someone she describes as being like a “jazz-lounge-lizard” – and loved it, relishing the freedom it offered compared to the big choirs. “They wore robes, but we got to wear silk blouses, mini skirts and four-inch heels. That was my thing.” Up and down the country they won almost every competition they entered. As the lead soprano, she went on to win the Grand Prize at the All-American Music Festival at Disney World Orlando. “I beat out a thousand kids or something like that.” A bigger break beckoned when, after her stint in the Twelve Oaks Youth Pops Orchestra, performing in malls across the country – one imagines like a young Tiffany – she was invited to California by an impresario who told her parents, “I think we can really do something with her.” Though old enough to travel of her own volition, she listened when her parents refused. Looking back, she reflects, “I could have ended up like Mariah or Whitney.”

“It had to be soul… with that real love for the music.”

Despite holding down a career outside the industry, her creativity hasn’t been limited to music – she was once hired as a comic illustrator by Dark Horse for ElfQuest, before rights issues stalled the project – yet her passion for music has always pulled her back. With world music band Zebula Avenue, she wrote “I Know a Way”, later chosen by the Democratic National Convention for a CD supporting Barack Obama. The inspiration for Zebula Avenue’s “Life Will Be Fine” – written about a relationship Honoré had, pre-Kevin – would also serve as the basis for “It’s Over”.

“It was about the great horrible breakup of 2001,” says Honoré. “We were together eight and a half years. At year six, I asked him to marry me. He said, ‘It’s not no, but not now.’ I hung on two more years, then my dad said, ‘When a man wants you, he has no impediments.’ I’d already died once, but breaking that relationship off was harder.”

A co-write with Tim Bovaconti, “It’s Over” is a pocket masterpiece – four and a half minutes of sweet soul magic, opening with a brass fanfare that Honoré likens to “a seventies news report theme.” Her voice soars with poise and dignity, weaving through strings before the track swells into a rousing, handclap-driven anthem.

When presented with the backing vocal arrangement, Thom said was blown away. Says Honoré: “I brought all these ideas and asked him, ‘So, which one?’ He simply replied, ‘Yes.’ Thom made all the difference.” The background vocals provide the light at the end of the tunnel, looking ahead to her new life with hope: “Moving on, love is strong – next time’s gonna be sweeter.”

It all circles back to her happiness in Canada with her husband. “Following my break-up, my mom was the first to scoff and say, ‘There’s no damn way you’re gonna get everything you asked for. You wanted someone kind, no kids, nice job, never married – and you have the nerve to ask for him to be handsome too!?’ But God knows me and God provides – He’s not gonna stick me with somebody I can’t look at!”

After meeting her soulmate, she felt emboldened to make the music she’d always loved. “The Yup’ik people have a word – Agayuliyararput – it means my way of making prayer. That’s what this music is for me. These chords are my way of mainlining the divine.” In another universe this could have been the debut of a jazz chanteuse, but Honoré believes everything happens right on time, guided by something greater. “It could have been jazz or yacht rock – but as a Black kid from Detroit, it had to be soul.”